Decoding Maga

The Word “Maga” — A Journey Through Language, Culture, and History

Language is not static. It moves like a river, carving out meanings, shifting connotations, and carrying deep histories underneath the surface.

One such word, deceptively small but richly layered, is the Latin “maga” — a term that calls to mind ancient rituals, divine mysteries, and evolving interpretations across millennia.

In this article, we will explore the Latin background of “maga,” trace its roots through earlier civilizations, examine its appearances in classical literature, and consider the legacy it has left on the modern imagination.

1. The Origin: Persian Fire and the Magi

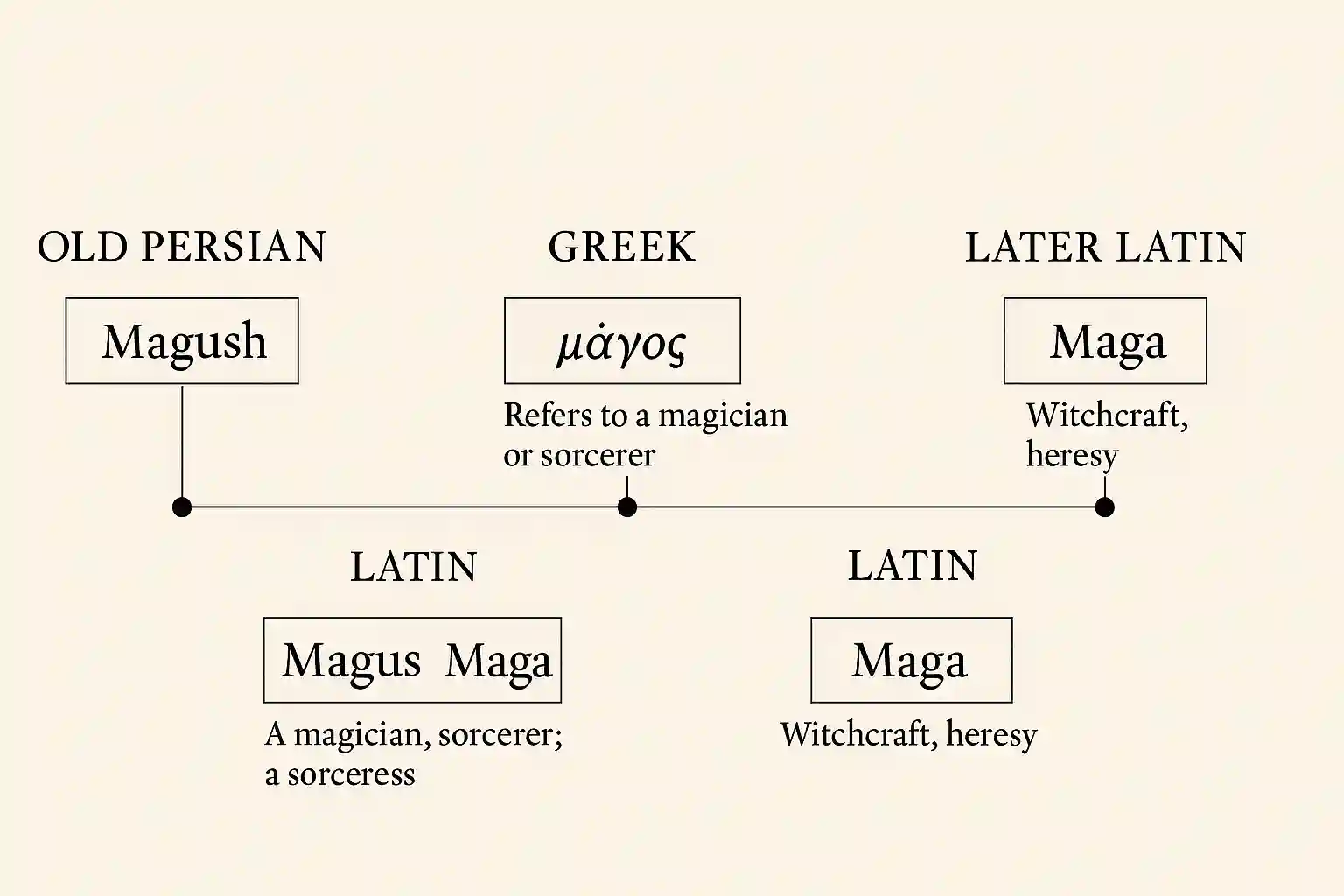

Before “maga” became a Latin word, it was part of an even older linguistic tradition. The root of magus — from which maga is the feminine form — lies in the Old Persian term magush (𐎶𐎦𐎢𐏁).

In ancient Persia, the Magush were a tribe or caste of priestly specialists. They oversaw religious ceremonies, particularly those involving fire, and played significant roles in the Zoroastrian faith. These priests were not “magicians” in the later, sensational sense; rather, they were considered custodians of sacred wisdom — guardians of rituals, astronomy, and dream interpretation.

The Greek world encountered these Persian priests during periods of cultural contact and conflict, notably during the Greco-Persian Wars. The Greeks, fascinated and sometimes suspicious of foreign religious customs, adopted the term μάγος (mágos), and broadened its meaning to include anyone perceived to practice exotic or mysterious arts.

Thus, in Greek, magos could refer to a Persian priest, but also a magician, a seer, or a charlatan.

2. The Transition to Latin

The Romans, inheriting so much of their literary and philosophical vocabulary from the Greeks, absorbed magus into Latin without significant alteration.

In Latin, we find:

- Magus (masculine noun): a magician, sorcerer, or wise man.

- Maga (feminine noun): a female magician, a sorceress.

The forms declined in regular first and second-declension patterns:

- Singular: maga (nominative), magae (genitive)

- Plural: magae (nominative), magarum (genitive)

Thus, when a Roman spoke of a maga, they referred to a woman reputed to use magical arts, whether for healing, divination, enchantment, or maleficium (harmful magic).

3. Context Determines Meaning

In classical Latin literature, “maga” could carry either a neutral or a negative meaning, depending on the author’s view of magic and its practitioners.

- In some cases, a maga was simply a wise woman, a practitioner of ancient rites, akin to a priestess or a healer.

- In others, especially in the Christianized Latin of the later Roman Empire, the word leaned heavily toward negative connotations — synonymous with witchcraft, heresy, or forbidden arts.

This duality — wisdom versus deception, healing versus harm — threads through every mention of magi and magae in the surviving texts.

4. “Maga” in Classical Latin Texts

Let us now turn to some concrete examples where “maga” appears in authentic Latin writings.

One notable occurrence is in the poet Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” where he speaks of magical transformations and enchantresses who change the natural order:

“Estne aliquis vestrum, magna qui maga verba noverit?”

(Is there among you anyone who knows the great words of a powerful maga?)

— Ovid, Metamorphoses (adapted for clarity)

Ovid here uses maga in a context suggesting wonder and awe — not yet outright condemnation.

Another famous literary figure associated with the feminine use of magic is Circe, the sorceress from Homer’s Odyssey, later adopted into Roman mythology. Though the Latin texts often describe her as a “venefica” (poisoner) or “maga,” the portrayal is complex: Circe is a figure of both seduction and wisdom.

In Roman satire, especially in the writings of authors like Horace, the maga appears more suspiciously, often linked with themes of manipulation, seduction, and sometimes outright evil. In Satires 1.8, Horace describes witches performing dark rituals in the dead of night, invoking the spirits of the dead.

Here, the maga is no longer a neutral wise woman but a threatening figure associated with death and disorder.

5. Christian Transformation of the Term

As Christianity rose to dominance in the Roman Empire, the vocabulary around magic shifted dramatically.

Whereas earlier cultures could regard magicians and priestesses with a mixture of respect and fear, the Christian worldview increasingly painted all such figures in a starkly negative light.

Magus and maga became terms of denunciation:

- A magus was a sorcerer consorting with demons.

- A maga was a witch practicing forbidden rites, often punishable by death.

Ironically, the Magi — the “wise men from the East” who visited the newborn Christ — are treated positively in the Gospel of Matthew. Early Christian commentators labored to distinguish between the “good Magi” (who recognized Christ’s kingship) and the “bad magi” (pagan sorcerers).

Thus, context remained everything.

6. The Legacy of “Maga” into Later Languages

From Latin, the concept of the maga drifted into medieval and modern European languages:

- In Spanish and Italian, maga still means “sorceress” or “female magician.”

- In French, the word is magicienne (derived from magicien, from magus).

- In English, while “maga” itself is rare, its root “mag-” survives in “magic,” “magician,” and related words.

It is notable that in many of these languages, the feminine aspect of magical practitioners often carried more suspicion and danger — a reflection, perhaps, of broader cultural anxieties about women and power.

7. Conclusion: The Deep Power of Words

The word “maga” reminds us that language, magic, religion, and gender are deeply intertwined in human history.

To the ancient Persians, the Magush were sacred keepers of divine mysteries.

To the Greeks, the magos was a figure of fascination and occasional fear.

To the Romans, the maga could be a healer, a seductress, a seer, or a witch.

To medieval Christians, she was a heretic and an enemy.

Today, fragments of these old meanings survive, often unnoticed, in the words we use for magic, mystery, and wonder.

In every age, the figure of the maga — the wise woman of power — both terrifies and attracts. She embodies the unknown, the uncontrollable, and the possibility of transformation.

Whether seen as a villain or a visionary, the maga is an archetype that endures.

References:

- Ovid, Metamorphoses.

- Horace, Satires.

- Cicero, De Divinatione.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History.

- New Testament, Gospel of Matthew.

- Encyclopedic entries on Magi and Magic in the Oxford Classical Dictionary.

Part 2

The Spoken Word: “Maga” and the Spiritual Reality of Naming

In the ancient world, words were not merely sounds — they were forces.

Speaking a word was an act of creation, invocation, or authority. In Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and many mystical traditions, it was widely understood that to name something was to call it forth or exercise power over it.

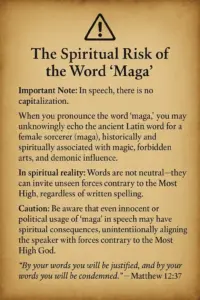

In this deeper spiritual context, your observation is crucial:

- In speech, there is no distinction between lowercase and uppercase.

- Thus, pronouncing “maga” aloud carries no visible “protection” or “signal” that you mean only a harmless political slogan.

- Instead, the raw sound maga resembles ancient names or titles connected with magic, sorcery, and spiritual rebellion against the Most High God.

Ancient Views on Spoken Magic

Both Jewish and early Christian traditions warned against:

- Using names associated with foreign gods (Exodus 23:13: “Make no mention of the names of other gods…”).

- Invoking spiritual forces unintentionally through careless words.

- Engaging in magical practices by verbal formulas (which often began simply by naming the spiritual entity).

In Latin, Greek, and earlier traditions, sorcerers (magoi and magae) were believed to:

- Summon spirits by speaking their secret names.

- Exercise control or open portals by uttering ritual words.

- Bring spiritual forces into the physical world by precise spoken incantations.

Thus, spiritually speaking, uttering the sound “maga” — intentionally or carelessly — could function as a kind of verbal opening to spiritual influences, especially if spoken repeatedly, chanted, or invested emotionally.

The voice gives shape to unseen realities.

Practical Spiritual Reflection

In spiritual wisdom, especially among the early followers of Yeshua (Jesus), careful speech was emphasized:

- “Let your speech always be with grace, seasoned with salt…” (Colossians 4:6)

- “Death and life are in the power of the tongue…” (Proverbs 18:21)

Therefore, believers, seekers, and the spiritually aware must exercise discernment:

- Understand what your words historically and spiritually carry.

- Avoid invoking or giving legal ground to spiritual forces opposed to the Most High.

- Remember that invisible realms respond to sounds and intent, not to spelling or capitalization.

In Summary:

| Aspect | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Political spelling (MAGA) | Acronym: “Make America Great Again” (capitalized for political emphasis) |

| Spoken sound (maga) | Matches ancient term for sorceress; no visual capitalization in speech |

| Spiritual principle | Speech can summon, create, or open spiritual realities |

| Caution advised | Words have power beyond human understanding; unintentional invocation is possible |

Final Word

In spiritual matters, nothing is “just a word.”

Names, sounds, invocations — all carry weight in the unseen world.

Thus, when speaking, especially in sensitive spiritual times, we are wise to remember the ancient counsel:

“Set a guard, O LORD, over my mouth; keep watch over the door of my lips.” (Psalm 141:3)

More Resources

Discover more from Master Yahshua Messiah

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.