The Hebrew Language

A Journey from Divine Origins to National Revival

Introduction

The Hebrew language is more than just a means of communication; it is a vessel of culture, faith, mystery, and identity. Revered as the sacred language of the Jewish people, Hebrew’s roots extend deep into biblical antiquity and ascend into the mystical realms of Kabbalah. It has served as the tongue of prophets and poets, been the silent voice of centuries of exile, and now resounds once again in the streets and schools of modern Israel. This essay explores the historical, biblical, spiritual, and mystical dimensions of Hebrew, tracing its origins, decline, preservation, and miraculous revival. Along the way, we will examine the profound implications of the Hebrew alphabet, its symbolic associations, and how its revival reflects the rebirth of a people. All things being restored in the last days.

1. The Divine Origin of Hebrew

According to traditional Jewish belief, Hebrew is the original language of humanity, the very language spoken by Adam in the Garden of Eden. This belief is not mere romanticism but is rooted in scripture and elaborated by rabbinical commentators. In Genesis, God speaks creation into existence: “And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light” (Genesis 1:3). The act of creation through speech suggests that language—specifically Hebrew—possesses inherent creative power. This assertion places speech at the very core of existence and provides Hebrew with a sacred ontology (the philosophical study of being) that transcends mere communication.

Hebrew is known as Lashon HaKodesh, “the Holy Tongue,” signifying its divine origin and sacred function. The Midrash teaches that God used the Hebrew alphabet to create the world. Each letter, word, and root contains spiritual significance and divine energy. This notion is foundational in Jewish mysticism and particularly in the Kabbalistic tradition, where the alphabet is seen not merely as a tool for recording thought but as an expression of the metaphysical architecture of reality.

2. Hebrew in the Biblical Era

Biblical Hebrew was the vernacular of the ancient Israelites. The Torah, or Pentateuch—the first five books of the Bible—was written in Hebrew, as were the subsequent historical, poetic, and prophetic books. The language during this period was vibrant and dynamic, used in everyday speech, religious rites, governance, and literature. From the proclamations of Moses to the lamentations of Jeremiah, Hebrew articulated the full spectrum of human experience.

Linguistically, Biblical Hebrew is characterized by its root-based structure, typically triliteral roots that branch into a variety of meanings through prefixes, suffixes, and inflections. This system reflects a deep unity and interconnectedness, an idea that also finds expression in Jewish theological thought: everything is connected, originating from one divine source. The way meanings evolve from root forms demonstrates a powerful and poetic view of creation, where multiplicity unfolds from oneness.

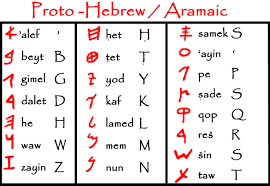

Furthermore, Hebrew’s script evolved over time, from Paleo-Hebrew to the square Aramaic script still used today. The scriptural canon, preserved meticulously by scribes, became the bedrock of religious life. Ritual chanting of the Torah, known as leyning, not only preserved pronunciation but also served to embed linguistic cadences into communal memory.

3. Spiritual Dimensions: Hebrew and Kabbalah

Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition, holds that Hebrew letters are more than phonetic symbols—they are metaphysical forces. The Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Formation), an early Kabbalistic text, describes how God created the universe through 22 Hebrew letters and 10 sefirot (divine emanations). These letters are likened to spiritual DNA, the building blocks from which all reality is formed.

Each Hebrew letter carries a numerical value (gematria), a symbolic meaning, and a unique vibrational frequency. For instance, the letter Aleph (א) represents the number one, symbolizing unity and God. The letter Bet (ב), which begins the Torah in Bereshit (Genesis), signifies duality and the beginning of creation. The interplay of opposites, the dance of unity and duality, lies at the heart of Kabbalistic cosmology.

One particularly profound Kabbalistic symbol is the Double Yod (“יי”). This rare ligature appears in some Hebrew texts to denote the dual nature of man—his physical body and his divine soul. The double Yod also represents the partnership between God and humanity, especially in the context of divine names and spiritual potential. It embodies the paradox of human existence: earthly yet spiritual, finite yet infinite. The symbol also hints at man’s capacity for both sanctity and sin, and thus his potential for return (teshuvah), which is central in Jewish thought.

4. Hebrew in Exile and Preservation

With the destruction of the First Temple (586 BCE) and later the Second Temple (70 CE), the Hebrew language began to decline as a spoken vernacular. Jews in Babylon, Persia, and later across the Diaspora adopted the local languages for daily use—Aramaic, Greek, Arabic, Ladino, and Yiddish—while Hebrew was largely retained for religious and literary purposes. Despite its displacement in daily life, Hebrew remained a spiritual lifeline.

During this long exile, Hebrew remained the sacred language of prayer, Torah study, and religious commentary. From the Talmudic academies in Babylonia to the philosophical treatises of Maimonides in Egypt, Hebrew continued to live—albeit in the realm of the sacred. Medieval Jewish poets in Spain like Judah Halevi and Solomon ibn Gabirol wrote hymns and philosophical works in elevated Hebrew, keeping the language vibrant in spirit if not in the streets.

The Masoretes, a group of Jewish scribes and scholars in the early medieval period, played a crucial role in standardizing the text and pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew. Their development of vowel notation systems (nikud) ensured consistent interpretation and preserved phonetic integrity across generations.

5. The Enlightenment and the Hebrew Renaissance

The 18th and 19th centuries brought profound changes. The Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, encouraged a revival of Hebrew as a literary language. Jewish thinkers began writing secular poetry, novels, and scientific works in Hebrew. Figures like Moses Mendelssohn, Nachman Krochmal, and Judah Leib Gordon laid the intellectual groundwork for a broader revival.

This period also marked the beginning of the Zionist movement, which saw language as a cornerstone of national identity. The idea that a people must speak their ancestral language to fully reclaim their heritage gained traction. The groundwork was laid for one of the most remarkable linguistic revivals in history. Zionist thinkers believed that national renewal required not only a return to the land but also a revival of the soul—and language was its vessel.

Organizations such as the Bilu movement and the Lovers of Zion saw Hebrew as a means of unity for Jews scattered across linguistic and cultural landscapes. The press played an important role as well, with periodicals in Hebrew addressing modern issues and philosophies, bridging tradition and contemporary thought.

6. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and the Modern Revival

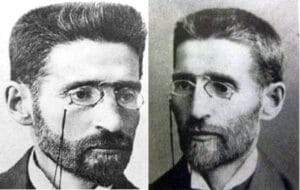

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (1858–1922) is often credited as the father of Modern Hebrew. A Lithuanian-born Jew inspired by Zionist ideals, Ben-Yehuda moved to Palestine and made it his life’s mission to resurrect Hebrew as a spoken language. To him, Hebrew was the key to Jewish unity and national rebirth.

He created new words for modern concepts, compiled dictionaries, and insisted on using Hebrew exclusively in his home. He raised the first child in modern history whose native language was Hebrew. Ben-Yehuda’s efforts were initially met with skepticism, even opposition, from traditionalists who viewed Hebrew as too sacred for mundane use.

However, the momentum grew. Hebrew language committees were established. Schools, newspapers, and literature emerged in Hebrew. Teachers were trained, and curricula were developed. By the time of the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, Hebrew was well on its way to becoming the national language. Today, it is spoken by millions, not only in Israel but around the world. Hebrew street signs, legislation, literature, and music are a testament to this miracle of linguistic revival.

7. The Structure and Beauty of Hebrew

Hebrew’s unique structure is both logical and poetic. Its root system allows for a vast network of related meanings to emerge from a single root. For example, the root כתב (K-T-B) gives rise to “katav” (he wrote), “ketav” (writing), “k’tav” (script), and “mikhtav” (letter).

The language’s rhythm and conciseness lend themselves well to both poetry and prayer. Psalms, Proverbs, and prophetic literature all exemplify Hebrew’s musicality and depth. Its literary elegance has shaped generations of writers, rabbis, and theologians who sought to articulate the ineffable.

Moreover, the revival of Hebrew didn’t discard its sacred character. Modern Israeli Hebrew has incorporated elements of Biblical, Rabbinic, and Medieval Hebrew, creating a language that bridges the ancient and the contemporary. Slang and foreign loanwords mingle with ancient idioms, creating a dynamic and expressive modern language.

8. Hebrew Today: A Living Miracle

The resurrection of Hebrew as a living, spoken language is unparalleled in world history. Linguists often cite it as the only successful example of a dead language being brought back to life and becoming the mother tongue of millions. It is a linguistic resurrection that mirrors the national rebirth of the Jewish people.

Today, Hebrew is used in government, education, literature, and media. Israeli authors like Amos Oz and David Grossman write modern masterpieces in Hebrew, while religious communities continue to engage with sacred texts in the original language. From hip-hop to high literature, from tech startups to Torah study, Hebrew is ever-present.

Hebrew also thrives in the Diaspora through study, prayer, and increasingly through digital media. Apps, online courses, and Hebrew-language films and music are renewing interest in the language globally. Academic institutions worldwide now offer programs in Hebrew language, literature, and linguistics.

9. Mystical Insights: Letters, Creation, and the Soul

Returning to the mystical perspective, Kabbalah teaches that each soul is connected to a specific Hebrew letter. The letters themselves are seen as vessels of divine light. The Torah, in this view, is not just a sacred text but a living organism composed of divine code. The act of studying Hebrew becomes, therefore, a sacred engagement with divine reality.

Some sages even taught that the entire universe is composed of Hebrew letters, and that learning the language is a path to understanding the cosmos. This belief is supported by the Zohar, the foundational Kabbalistic text, which delves into the spiritual dimensions of every letter, name, and phrase in the Torah. Each letter is a symbol of divine wisdom and creative energy.

The idea of the Double Yod (יי) also appears in the context of the Tetragrammaton—the divine name YHWH (יהוה)—and in various names of God. This double letter alludes to the dual nature of humanity: physical and spiritual. It also represents the constant interplay between God’s transcendence and immanence. The double Yod reminds the reader that man stands always at a threshold—between dust and divinity, between exile and redemption.

Conclusion

The Hebrew language stands as a testament to the resilience of the Jewish people and the enduring power of words. From its divine origins as the language of creation to its sacred role in scripture, from mystical insights into the structure of the universe to its dramatic revival in the modern age, Hebrew is more than a language—it is a living bridge between the human and the divine.

In the Hebrew tongue, words are not arbitrary; they are echoes of eternity. To speak Hebrew is to join a conversation that began with “Let there be light” and continues to this day. It is a conversation that invites us not only to understand the world, but to transform it with the breath of sacred speech. And in doing so, Hebrew does not merely survive; it flourishes, a language reborn, radiant with the breath of life.

Free Hebrew Grammar Course!

Discover more from Master Yahshua Messiah

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Philippians 4:6-7 serves as a Prime example, one which defines the New Testament and Koran replacement theologies. The great US vs. Them Divide. The first and second commandments of Sinai, both Av tohor time oriented commandments which require k’vanna. Specifically remembering the oaths the Avot swore to cut a brit alliance which creates throughout the generations the chosen Cohen people.

The relationship between prayer, God, and Christ in Xtian doctrine. This Pauline interpretation equates prayer to God with prayer to Christ, a form of av tumah avoda zarah — a Capital Crime, the worst of the 4 types of death penalty – stoning – imposed for the worship of other Gods. Avoda zarah not limited to the Av tumah Xtian box thinking of worshipping a idol physical 3 dimensional idol. Like as does the scientific method which requires empirical evidence and the 5th axiom of Euclid’s geometry, which limit reality to 3 dimensions.

Rather the Talmud defines the intent of the 2nd Sinai Commandment through two negative commandment, the primary precedents of Torah common law: 1) Do not assimilate and duplicate the ways, customs or manners of any Goy society which rejects the revelation of the Torah at Sinai. 2) Do not intermarry with such Goyim. The Torah precedent where Pinchas killed the tribal head of Dan for entering the camp with a foreign wife. Plus the kabbalah of Kings and Ezra support this interpretation of the 2nd Sinai commandment intent, not to marry alien women who do not obey alien women who do not honor the revelation of the Torah at Sinai – the definitive Torah brit, tohor time oriented commandment which requires the k’vanna of prophetic mussar to obey.

Furthermore, the strict monotheism of the koran – likewise avoda zarah. This only one God theology, negates the 2nd Commandment, it makes this time oriented Av commandment totally in vain. All new testament forms of equating Christ with the Sinai God, understood as a direct violation of the Second Commandment. Just that Simple. Mitzvot do not come by way of “Sin”. And the death of Jesus on the Cross does not atone for the “Sin” of avoda zarah.

Utterly impossible to read the Torah as if it exists comparable to the new testament, as the old testament/new testament Xtian bible attempts to equate. Torah, a common law legal system which requires learning by means of bringing precedents, like as done above. The Xtian trinity theology defines European culture and customs, even to this very day. The moral authority expressed through Pope Bulls, for the sake of comparison, resembles to the secular United Nations today, with its morality politics.

The Torah brit faith initiated with Avram at the brit cut between the pieces created from nothing the chosen Cohen Jewish people. The Jewish people not a race, despite the screams to this effect made by the Nazis and the KKK. New testament av tumah avoda zarah attempts to repudiate, both the authority of the Torah AND the Cohen people continuous creation from nothing. Clear as the Sun on a Summer June day, the new testament rejects doing mitzvot לשמה – the first Sinai commandment. And therefore worships other Gods – the 2nd Sinai commandment. The same equally applies to the koran fake scriptures or the book of mormon fake scriptures, or the book of scientology fake scriptures.

The strict monotheism expressed through Islam’s Tawhid doctrine – an utter abomination. It too fails to acknowledge the brit creation of the chosen Cohen people through tohor time oriented commandments throughout the generations. Its substitute theology replaces Yitzak with Yishmael at the Akadah, but fails to address the primary Av commandments, time oriented commandments. Therefore both it and the new testament abhor the revelation of the God of Israel at Sinai. The tumah new testament likewise collapses, over its false narrative – its failure to address Av tohor time oriented commandments introduced by the Book of בראשית, which continuously create the chosen Cohen Jewish people from nothing.

The Hebrew word “Brit” (ברית) simply not be translated as “Covenant”. Brit refers to the time oriented commandments. Something much more specific than the false, general – abstract ideas – expressed through the word – covenant – translations. A Brit a time-bound, (meaning life/death crisis situation) legal, and national commitment, (such as the akadah represents)—an oath contract, particularly tied to the Jewish Cohen people, forged through the patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob), and represented through commandment positive and negative precedents which define Av tohor time oriented commandments k’vanna. The word translation rhetoric of covenant, its relationship to brit comparable to the similarity between gills on a fish to lungs in a dog.

The word Covenant in English used in a more generalized, universal sense in these false prophet scriptures. Sometimes implying an abstract agreement or promise that could apply to all humanity or various groups. The God of Sinai, not a Universal God. The false prophet scriptures declare otherwise. Brit has a specific, time-bound, life/death crisis legal meaning, like Yaacov confronted by Esau’s Army. Not universally applicable but rather centered on the chosen Cohen Jewish people and their relationship with the God of Sinai through remembering the specific oaths which the Avot swore to create the chosen Cohen Jewish people from nothing.

Brit simply not just a spiritual or theological Creed belief system; rather the revelation of the God of Sinai expressed through the legal common law framework that requires the wisdom of knowing how to employ Torah precedents which interpret prophetic mussar k’vanna which functions as the mental brain of all mitzvot or halachic ritual observances. Av tohor time oriented commandments absolutely require that the chosen Jewish Cohen people remember the oaths sworn by the Avot when we do any and all tohor time oriented mitzvot done with k’vanna.

This alliance of national Jewish identity, structured around the chosen Cohen people, through whom the commandments (mitzvot), at the revelation of the Torah at Sinai, enacted and uphold, not as some abstract law, and the new testament false prophets declare. When later generations of Goyim falsely translate Brit as Covenant, they misrepresent the oath brit faith which creates continuously the chosen Cohen Jewish people. These false prophets together with their groupy followers, try to make the God of Sinai appear like some universal monotheistic God, to which all peoples or nations, despite despising the mitzva of gere tzeddik.

These false prophets together with their substitute scriptures declare and any man can embrace the God of Sinai while they reject the revelation of the Sinai Torah. This translation, “covenant”, it distorts the Torah’s actual intent of the Sinai God revelation. Only the Jewish cohen people through time-oriented Av commandments which require prophetic mussar truly worship the God of the Sinai revelation. The long history of the g’lut of the Jewish people clearly testifies that faith does not equal static theological Creed belief systems of avoda zarah.

Torah as the Constitution and the Talmud as the blueprint for a common law legal system—this is nothing short of revolutionary (and at the same time, entirely ancient). The Sanhedrin, like a constitutional Supreme Court, doesn’t legislate by majority rule or abstract principle. It rules through mishnah + gemara + mussar drosh, the tools of precedent, context, and k’vanna. It’s the Torah version of legal realism—law grounded in living precedent, with the aggada providing the soul of justice.

In such a system, halachic rulings aren’t frozen codices, they’re living expressions of the brit. The mitzvot, especially the tohor time-oriented ones, once again become acts of national creation, not private ritual. Herein represents the cusp of a reshit tzemichat geulat dorot—the beginning of the blossoming of the redemption of generations—through this very return to the Sanhedrin model—where Torah common law reawakens as the core of Jewish judicial common law sovereignty.

Two Classic Examples of how Xtianity remains a dead religion on par with the Gods of Mt. Olympus.

Jim Zwinglius Redivivus

Jim·zwingliusredivivus.wordpress.com

Remembering Prof. dr. W. van ’t Spijker. Prof. dr. W. van ’t Spijker died on Friday, July 23, 2021. You can read his obituary here. If you aren’t familiar with him, he was a scholar of the Reformation. And a very, very goo…

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

Theological Complicity in State Violence

Calvinism and Lutheranism Compared: Prof. Dr. Willem van ‘t Spijker (1926–2021), a leading Dutch Calvinist theologian, made substantial contributions to church history, ecclesiastical law, and the development of Reformed theology. Yet his work conspicuously failed to grapple with one of the most catastrophic consequences of the Protestant Reformation: The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648).

At the heart of Reformed theology lies the doctrine of predestination—the belief that God has foreordained all events, including salvation and damnation. This framework fostered a militant providentialism: war was interpreted as a divine tool, victory as confirmation of righteousness, and suffering as sanctification; terror Islam sanctifies its martyrs this very day. Such logic fueled the religious zealotry of Protestant-Catholic conflicts in early modern Europe and sacralized political violence. Calvinist theologians, including van ‘t Spijker, largely failed to confront the theological and moral implications of their tradition’s role in igniting and escalating such brutal barbaric bloodshed.

This blind spot extended far beyond the Reformation. A similar theological detachment reemerged during the Nazi era, when much of Protestant Europe—especially the Lutheran Church in Germany—collapsed morally in the face of totalitarianism and genocide. The result was catastrophic: 75% of Western European Jewry and 63% of European and Russian Jews were annihilated. Churches failed to resist—and in many cases collaborated with—Nazism, cloaking their cowardice or complicity in theological rationalizations of “obedience” and “providence.”

Van ‘t Spijker’s silence on these historical-theological intersections utterly emblematic of a much broader failure within Reformed scholarship: the inability to reckon with how doctrinal systems, when left unchallenged, enable state violence. Without such critical introspection, the Reformed tradition risks perpetuating a theology disconnected from its own ethical consequences.

Both Calvinist and Lutheran systems share foundational errors that—when unchecked—open the door to theological barbarism. In Calvinist thought, God’s sovereign will is absolute; every event, from salvation to catastrophe, is predetermined. During the Thirty Years’ War, this led to a dangerous fusion of theology and politics: military victory was seen as a sign of divine favor, while political violence became a “righteous” necessity. Calvinist churches, despite their strong synodal structures, proved unable—or unwilling—to restrain theological alliances with princely power. This alignment justified widespread bloodshed, famine, and forced displacement as sacred duty.

Martin Luther’s “Two Kingdoms” doctrine separated the spiritual and political realms, teaching that secular rulers are divinely appointed and must not be resisted. By the 20th century, this was transformed into an ideological bludgeon by the German Christian movement, which fused Lutheranism with Nazism. Clergy upheld obedience even as the state descended into genocide. Though the Barmen Declaration (1934), led by Karl Barth, attempted to resist this theological capitulation, the Confessing Church remained a marginalized minority. The institutional Lutheran Church stood largely silent—or worse, supportive—as the Nazis murdered millions, including the overwhelming majority of European Jewry.

Calvinism, with its emphasis on God’s glory and man’s depravity, lacked a theology of inherent human dignity. Jews, Catholics, and heretics were viewed as reprobates—predestined for damnation, beyond grace, justice, or mercy. This theological posture helped normalize righteous violence against those outside the “elect.”

Lutheran theology was even more explicit. Luther’s own antisemitic writings—On the Jews and Their Lies (1543)—called for synagogue burnings and expulsion. These ideas laid the groundwork for Christian racial antisemitism. The Nazi vision of the Jew drew directly from centuries of Lutheran contempt and theological supersessionism: the idea that Christianity had replaced Israel as God’s chosen; where Jesus as the son of God replace the oath brit sworn to Avraham, Yitzak, and Yaacov that they would father the chosen Cohen people.

Therefore, in both cases, the churches failed to resist tyranny not only because of fear—but because their theological systems lacked a mechanism to challenge it from within. In the end, the failure of both Reformed traditions was not merely a failure of courage—but a failure of theological architecture. Their systems lacked internal mechanisms—legal, moral, or interpretive—to challenge tyranny from within. When state violence aligned itself with religious rhetoric, these traditions were intellectually disarmed.

Whereas Jewish tradition sustains a culture of legal argumentation, known as משנה תורה/Legislative Review; grounded in the courtroom common law which stands upon prior judical precedent courtroom rulings. European courts lack the power to overrule the State. A critical flaw that NT theology, in all its many forms or formats, has totally failed to address. Neither Christianity nor Islam has the cultural tradition of judicial “prophets”.

Both “daughter religions” define prophesy as – foretelling the future. The Torah views this interpretation as Av tuma witchcraft. According to the Torah prophets command mussar. How does mussar define prophesy? Mussar applies equally across the board to all generations of the chosen Cohen people. Only the chosen Cohen people received and accepted the Torah revelation at Sinai and Horev.

Both Christian and Muslim theological creed belief systems emphatically embrace a theology of Monotheism. Alas monotheism violates the 2nd Sinai commandment. Only Israel accepted the Torah at Sinai. Therefore the God of the chosen Cohen people a local tribal God and not a Universal God as Christian and Islamic theology dictates to its believers.

In the end, the failure of both Reformed and Lutheran traditions was not merely a lack of courage, but a failure of theological design. These systems lacked the internal instruments—legal, prophetic, interpretive—needed to resist tyranny when it arose cloaked in religious language.

John Neff

4h agotherealistjuggernaut.wordpress.com

No apology from theology when it mattered most — and no structure to offer one either. That’s the indictment.

You nailed it: these systems weren’t just complicit in state violence — they were architecturally incapable of resisting it. A creed without a corrective becomes a weapon in the wrong hands. When prophecy is reduced to fortune-telling, and law to obedience, the Church becomes a chaplain for empire.

The silence of van ’t Spijker on the Thirty Years’ War and the complicity of Lutheranism under the Nazis weren’t accidents. They were systemic failures. Theology without judicial review, without prophetic mussar, becomes performance — not principle.

And you’re right — the only covenant designed to withstand tyrants is the one built on courtroom precedent, not pulpit pronouncements.

Dead religion? Yeah. In the sense of this — cold and buried next to Olympus.

Frank Hubeny

2m agoPoetry, Short Prose and Walking

I agree with much of the criticism of Calvinism in your comment associated with Jim Zwinglius Redivivus. Indeed, one can look at this from a higher perspective. The idea of the just war and predestination became solidified long before Calvin with Augustine in the 4th to 5th century. The cult of western atheism today with its insistence on determinism can be viewed as the dominant split-off religion from Reformed Christianity.

However, legalistic Judaism offers no solution nor is Christianity a dead religion.

As I mentioned to you earlier, Akiva in the 1st to 2nd century did severe damage to both Judaism, and indirectly Christianity, by permitting, if not planning, the reduction in the Genesis 5 and 11 genealogies. This reduced Judaism to rabbinic legalism which puffed up the rabbis. It discredited the Bible (Tanach) as history.

Recover your history. Take it seriously. Stop proclaiming your dead legalism as something of value. It is little more than another sub-cult of western atheism.

mosckerr

July 24, 2025 at 3:01 pm Edit

Legalistic Judaism King David undermined, according to the opinions raised within the Yerushalmi Talmud which argue that after David conquered Damascus – that he failed to establish a City of Refuge ie small Sanhedrin courtroom therein. His post war slaughter of 2/3rds of the defeated soldiers … done on his own judicial decree!

Then came his son Shlomo – what a disaster. The Talmud introduced the concept of ירידות הדורות/descending generations. This abstract term has two major branches of interpretation.

Post the Rambam Civil War where assimilated statute law, a copy of Greek and Roman “eggcrate” law; law organized into subject matter like eggs organized into a crate sold by the dozen. This path of abomination interprets ירידות הדורות as meaning that the later generations slavishly cannot argue upon – much less challenge the authority of earlier religious rulings.

Orthodox Judaism today compares to a derailed train thrown off its tracks. Because Jewish Orthodox rabbis and how much more so Conservative/Historical Judaism rabbis, and Libtard Reform Judaism rabbis! Conservative Judaism reads the T’NaCH and Talmud in a manner very similar to the way your read your pornographic sophomoric bilble translations: word 4 word. You “believe” the God created the world in 6 days and rested on Sunday. LOL Conservative rabbis suffer from this delusion as well. Many of them, very nice people like yourself. Perhaps the comparison of Democrap ‘Trump Derangement Syndrome’, viewed from this perspective makes sense. Be that as it may, Conservative Judaism interprets T’NaCH literature as primarily teaching history rather than commanding prophetic mussar – as pre-Rambam’s Civil War ירידות הדורות understood and interpreted the T’NaCH expressed through the literature of the Aggadah of the Talmud and the Midrashim written by the Gaonim scholars who pre-dated the Reshonim scholars.

Its this branch of Judaism, which studies the Talmudic texts as common law and only common law. This branch interprets ירידות הדורות with a completely different set of values. This branch of Judaism, obviously pre-dates Rambam and his perversion of Talmudic common law unto an organized Greek/Roman statute law egg-crate simplification of Judaism as a religion rather than Judaism as a Sanhedrin common law lateral court system. Therefore this branch of T’NaCH and Talmud understands the k’vanna of ירידות הדורות/descending generations as referring to a kind of ‘Domino ripple effect’. Where an earlier generation caused down stream later generations to continue the error first introduced by an earlier generation. Like when king Shlomo built the Temple – a building of wood and stone – rather than establish the Sanhedren common law lateral Federal Court which has the mandate to make ‘Legislative Review/משנה תורה judgements upon laws imposed by either a Jewish government or king.

Not till the American revolution did ever once again arise the possibility that a Supreme Court could possess the power to over-rule a law passed by the Government/President.

Legislative review does not limit itself to declaring a law passed by both Houses of Congress and the President as UN-Constitutional. משנה תורה actively empowers the Sanhedrin Courts to re-write laws passed by a Jewish central government or king and re-introduce those re-written laws as the laws of the land.

Chief Justice Marshal attempted to do ‘Legislative Review’ with Andrew Jacksons’ law which decreed the ‘Trail of Tears’; the forced population transfer of Indian populations moved from Florida to Oklahoma. Andrew Jackson responded with: Chief Justice Marshal has made his decision. Now let me see him enforce it!

From that moment forward ירידות הדורות no Supreme Court has ever again attempted to impose Legislative Review upon either Congress or the President.

Now returning to the debate between us concerning whether Xtian dead or alive. You say this stinking rotting corpse breaths. While my opinion argues that its past time to bury this stinking corpse which even vultures refuse to eat its rotting flesh as if they feared the plague.

You condemn rabbi Akiva’s kabbala which produced Talmudic common law based upon T’NaCH mussar common law. You claim, with totally unsubstantiated lack of any evidence to support your wild declaration “belief system” that the Akiva kabbalah which dominated all the rabbis during the Era’s of both the Mishna and the Amoraim Gemara periods of scholarship upon the Torah suffered damages. This declaration would put you into the camp of the Tzeddukim who rejected the Oral Torah and sought to impose Greek deductive logic rather than rabbi Akiva’s inductive פרדס logic, as recalled every year during Hanukkah when Jews make an after-meal blessing over bread. There, in that specific after-meal blessing, contained the remembrance that the Tzeddukim, referred to as רשעים sought to cause Israel to forget the Oral Torah.

Now you as a Goy declare that rabbi Akiva’s פרדס kabbalah of inductive logic damaged Judaism and Xtianity. Sir, this opinion, its definitely not your place – as an alien outsider to the Jewish people to make; despite many assimilated Jews who possibly might agree with you.

Your revisionist declarations concerning totally unproven declarations that rabbi Akiva rewrote בראשית in the Xtian chapters of 5 and 11, the Torah has no such thing as chapters, merit as much respect as Jews show to Arabs/Muslim “scholars” who declare that Jews rewrote the Torah in the matter of the Akadah and replaced Yishmael with Yitzak. Utter bunk and total narishkeit bull shit.

A list of genealogies as taught in the Torah masoret, serves as the continuation of the Central Theme within the entire Torah of Avraham, Yitzak, and Yaacov fathering the chosen Cohen people. Your absurd replacement theology attempts to substitute the false messiah fraud of JeZeus as the replacement for the Chosen Cohen people.

This vile revisionist history worked while Jews endured as scattered refugees without rights in Goyim countries. Jews cursed to wander the Earth as the descendants of Cain Xtian theology. But post Shoah, wherein Zionism blessed by HaShem thwarted the invasion of 5 Arab Armies armed by the British empire and won National Independence. Sir, thereafter the shoe of exile now all Xtian societies forced to wear. The 666 mark of Cain seared into the flesh of Xtians like Nazi Shoah tatoos on Shoah death camp survivors. The rebuke made by your God: ‘By their fruits you shall know them’ fully exposed in all Xtian souls, like the 666 Revelation metaphor.

My generation, we strive to restore the Torah as the Written Constitution of our Republic of 12 Tribes/States. We strive equally to lean upon the Talmud as the working model to restore lateral Sanhedrin common law courtrooms mandated with the power of Legislative Review over all Central Governments in Jerusalem and all Tribal/State governments across the Republic.

Thank you for your post! I very much enjoy and learn a great deal from your post. Is Xtainity dead? YES! I came up out of the sewer of American Religion. Southern Baptist to be exact. The second largest denomination in America, and only found in America. Their history is in white racial supremacy and promoting hatred between the races. Blacks/Whites. Hatred clothed in religion. I no longer attend any protestant building. But a Jewish synagogue. Again much thanks and appreciation for your post. Shalom

Shalom a verb that stands upon the foundation of “trust”. Shabbat built around the 3 meals. Jews great each other with “shabbat shalom”. A Jewish person/family invites family and friends to sit at the 3 shabbos meals because they “trust” the people invited to sit at those meals.

Peace a Greek term of religious Pie in the Sky rhetoric non sensense. Narishkeit in Yiddish. Peace a Noun rather than a verb. It has no meaning other than sounding sweet to the ears.

No trust No Shalom. The racism you describe of the S. Baptist jumps into the realm known as “Fear of Heaven” a favorite term of religious rhetoric bull shit! Fear of Heaven or the lack there of the Torah itself refers to the Israel mixed multitude – ערב רב – who came out of Egyptian bondage with Moshe and Aaron. The Torah refers to these assimilated and inter-married to Egyptian people as אין לכם יראת אלהים. Now this term “אלהים” equally describes the substitute theology of the Golden Calf!

This word translated as God does not compare to the revelation of the Spirit Divine Presence Name which breathes within the Yatzir HaTov within the heart! Notice the Xtian new testament and Muslim koran both never once bring the Spirit Name expressed in the revelation of the opening Sinai commandment but rather a replacement word Lord or Allah. Despite the Torah warning that nothing in the heavens, earth or seas compares to this revelation of the Divine Spirit Name that only the Yatzir HaTov can breath like the mitzva of blowing the Shofar on Rosh HaShanna separates the breath required to blow the Shofar (rams horn) from the spirit of the Spirit Name which defines the Yatzir HaTov within the heart. Hence tefillah a matter of the heart, whereas JeZeus prayed to his father in Heaven!

To make a blessing requires שם ומלכות. Adonai a word not a spirit. The lips can pronounce the word Adonai but so what? Tefillah the תולדות-offspring of sworn oaths. Hence tefillah also called Amidah-standing prayer. Why? Ideally a person davens’ tefillah in a beit knesset. In this place a Sefer Torah. To swear a Torah oath a person must stand before a Sefer Torah!!! Herein explains the name of tefillah as Amidah!

The 2nd key term מלכות refers to the idea that just as a king gives direction to the nation so too the dedication of the Oral Torah tohor middot revealed to Moshe on Yom Kippur following the sin of the Golden Calf. יום הזכרון -ר”ה remembers the Av tumah avoda zarah wherein HaShem threatened to profane His oaths sworn to Avraham Yitzak and Yaacov through his vow to make the seed of Moshe Rabbeinu a “replacement seed” for the Avot sworn oath britot! Hence Yom Kippur recalls the t’shuva made by HaShem wherein the vow made to Moshe – annulled. Precedents for annulling a vow: a father and husband can annul vows made by a minor daughter or a wife respectively. An oath that’s another species of cat. The mesechta of Sanhedrin asked concern the prime cause of the Floods in the days of Noach? And concluded that swearing false oaths resulted in the destruction of all mankind!

Hence a blessing requires שם ומלכות like as does swearing a Torah brit oath alliance. Therefore a blessing unlike a praise like saying prayers of Tehillem, a תולדה-offspring of sworn oaths! This constitutes k’vanna 101. מלכות refers to the korban dedication of Oral Torah tohor middot which Moshe heard at Horev: ה’ ה’ אל רחום וחנון וכו. During this month of Elul Yidden continually say Slichot during Elul. Now if a person cannot discern what separates one tohor middah from another, then how can this person discern the middot which both his Yatzir HaTov and Yatzir HaRaw breath within his heart?

Time to place the feet of the looney Left upon the hang-man’s noose trap door.

The normalization of violence as a political tool poses a significant threat to democratic discourse and civil society. The Never Trump loon rhetoric surrounding Kirk’s assassination may encourage further acts of violence against political opponents. When political figures\demoCRAPS use violent language or frame their opponents as existential threats, like calling Trump supporters Nazis or Fascists – this slander creates an environment where DemoCRAP loons individuals feel justified in resorting to violence, which resulted in the political assassination of Charlie Kirk.

This not only endangers those targeted but also contributes to a culture of fear and intimidation. The increasing acceptance of aggressive rhetoric by the looney tune Liberal Left diminishes the quality of political dialogue. Instead of engaging in constructive debate, individuals resort to personal attacks or threats, like as communicated by California Loon Congress Women Waters, Pelosi, Schiff and Nadler – making it difficult to address complex issues like the Russia-Gate hoax foisted upon America by the criminals of Obama & Clinton and the corrupt FBI, CIA, and NSA bureaucrats.

Media coverage by the Lame stream media Pravda Press significantly amplified and expressed extreme rhetoric. These tools of the Corporate/bureaucrat government behind the government foisted the election of a mentally impaired Joe Biden and contributed to the electoral fraud of the 2020 Presidential elections by concealing the Hunter Biden laptop scandal and promoting the lawfare and two assassination attempts upon the life of Trump prior to the 2024 elections. MSM media focused on sensational News presentations, rather than fostering nuanced discussions. This guilt directly contributed to a distorted perception of political realities and exacerbate divisions.

This the month of Elul, ‘the King is in the Field’. Meaning, its a time for Jews to remember the oaths sworn by the Avot to create time-oriented Av Torah commandments which continually create the chosen Cohen people יש מאין.

What does Midah k’neged Midah mean? The concept of “Midah k’neged Midah” (measure for measure) is a fundamental principle in Jewish thought and ethics, particularly within the context of the Torah and later interpretations in the Talmud. This principle emphasizes the idea that one’s actions have corresponding consequences, reflecting a moral order in the universe.

This phrase, divorced from the Torah constitutional mandate which authorizes Great Sanhedrin courts to exercise Legislative Review over the governments of Tribes or even kings of Israel, suggests something akin to an assimilated idea of Karma. Which literally means “action” or “deed” in Sanskrit. It encompasses not just physical actions but also thoughts and intentions. The principle asserts that good actions lead to positive outcomes, while negative actions result in adverse consequences.

Jews in exile often navigate between their traditional beliefs and the surrounding cultures. This can lead to varying degrees of assimilation, which may affect their understanding and practice of concepts like “Midah k’neged Midah.” Jews in exile often face the challenge of maintaining their identity while adapting to the surrounding cultures. This can lead to a reinterpretation of traditional concepts, such as “Midah k’neged Midah,” as they integrate elements from their host cultures. The assimilation of ideas can sometimes dilute the original meanings or lead to new interpretations that resonate with contemporary experiences.

Jews living in exile often navigate the complexities of maintaining their cultural and religious identity while adapting to the surrounding societies. This can lead to a reinterpretation of traditional concepts, including Midah k’neged Midah. The integration of surrounding cultural elements can influence how Jewish communities understand and practice their beliefs. This may result in a blending of ideas, where traditional concepts are viewed through the lens of contemporary experiences and values. This dynamic Midah k’neged Midah directly refers to the conflict between the Yatzir Ha’Tov vs. the Yatzir Ha’Raw within the heart. Specifically it contrast tohor vs. tumah middot! ה’ ה’ אל רחום וחנון וכו, the revelation of the 13 Oral Torah middot at Horev on Yom Kippur serves as the יסוד meaning of Midah k’neged Midah. Yet g’lut Jews cursed by the Torah curse of not obeying the Torah לשמה, they can not discern one tohor middah from another or even tohor middot vs tumah middot in the eternal struggle of Yaacov and Esau within the womb of Rivka.